19th century American culture had endless layers of social protocol. They used personal titles in family life: “Professor Cunningham, please pass the salt.” They used multiple initials in their full names: “W. E. B. DuBois”, or “D. E. Jannon.” They used elaborate circumlocutions, like saying “prestidigitation” instead of “magic trick.”

Manners were a big deal, so music respected protocol even when it was intended for partying. And that made it too stiff for our ears. Our ears expect music to breach protocol. We still care about hierarchy at the office, but we don’t want it on the dance floor. And there was a transitional time in music when hot sounds were rare and shocking.

The change to hot styles was related to blacks assuming cultural leadership. Throughout the 19th century blacks had been dominant among performers, even of styles we think of as white. Between 1893 and 1930, black musicians led the introduction of modern styles — ragtime in 1893, blues in 1914, and then jazz in 1917.

Here are four recordings from this transitional time. The last three are all from the killer Archeophone release Stomp and Swerve – American Music Gets Hot. Note that I’m using the versions hosted on archive.org, which are not as clean.

1902: John Phillip Sousa’s band plays Liberty Bell March. This is the point of departure.

1908: The Zon-O-Phone Concert Band plays Scott Joplin’s rag The Smiler. Notice how much more lively Joplin’s writing is than Sousa’s.

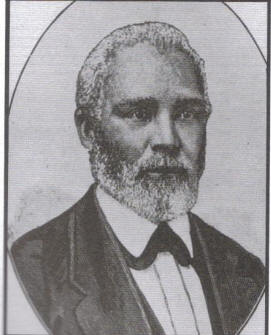

1914: Castle House Rag played by Europe’s Society Orchestra. Europe is James Reese Europe. His style was crazy hot and way before it’s time, analogous to early Stooges. Give this time to build to the climax and you’ll see what I mean.

1917: Livery Stable Blues played by the Original Dixieland Jass Band, a white act with plenty of sloppy enthusiasm but limited technique. This is the record that broke the hot style into the mainstream.